Bats in the Attic

A few nights ago, just as I was stumbling to bed, I heard something. It was a distinct fluttering sound–occasionally accented by a light thump. It was something I was able to place, all too well. A bat flying around our bedroom. Resigned to late-night adrenaline, I found an old blanket, wrapped the critter up, and released it in the backyard. Truth be told, it probably found its way back into my attic faster than I made it back to bed.

A little backstory is appropriate. We live in an old house in the central part of Springfield, IL. Lots of trees on the street. Lots of cracks in the old wood siding. Try as I might, I can’t seem to seal all of those cracks (probably has something to do with my ladder that doesn’t go all the way to the top floor, no jokes please). So. Much to my ongoing frustration. We get the occasional bat (or 3) in our attic. When it gets cold, they like to slip under the attic door and visit the warmer parts of the house. The thermometer read -17 F for at least two days last week…so it’s been cold.

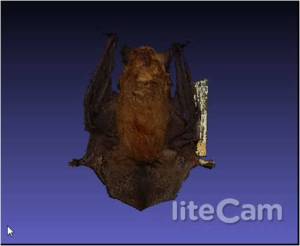

That said, a bat flying around our house in January surprised us. Bats are supposed to hibernate, right? A little judicious googling, and I found that this particular species, Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus), is no stranger to winter, and will occasionally move its winter roost, or fly around looking for something to drink on warmer days. No one told it that the Casa de Widga was closed for the season. Bats are interesting little critters. They’ve been around since the early Eocene (~52 million years ago). Even at that time they had already developed the capacity for winged flight–so they broke off from the more generalist mammal family tree even earlier. The species Eptesicus fuscus, like my midnight friend, has been in the Midwest since the Ice Age, the fossil record gets squirrely beyond that.

It’s probably appropriate that this little fellow came to visit me since we’ve been thinking a lot about bats lately. In 1999, ISM researchers Mona Colburn and Rick Toomey (now at Mammoth Cave National Park) visited a cave in Kentucky, only a few miles away from the main entrance to the world renowned Mammoth Cave. About 300 yards back into this cave, the trail cuts through a bank of sediment where to the naked eye–it looks like someone scattered a few boxes of toothpicks on the ground. Ok. So a LOT of toothpicks. Within these sediments are a series of bonebeds where thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of bats are deposited. It probably wasn’t a single event that did them all in. In fact, there are at least 11 different layers, each representing a different accumulation/concentration episode. Rick and Mona carefully excavated samples from each of the layers, brought them back to the ISM, screened away the sediment, and started trying to identify who’s who. This is easier said than done. The bat genus Myotis is very species rich (>100 species). Most of these species overlap significantly in size, show somewhat similar behavioral/roosting patterns, and most of the skeleton is morphologically indistinguishable between species. Those markers that distinguish living species of bats such as coat color or length, don’t help us much with fossil material. So out of >3000 bones recorded from the few gallons of sediment from bat cave, 7 species were identified (only 127 bones, <5% of the total). The rest were taxonomically ambiguous. Despite this, the sample is important to modern conservation decisions in the cave. In the early part of the 20th century, bat cave was blasted shut, and in 1937, flooded by the nearby Green River. Did the blasting and flooding have something to do with the mass bat deaths?

In 2008 we sent a few of these bones out for radiocarbon dating, with some surprising results. The uppermost bonebed dated to the late Holocene, ~2200 years ago, while the bottom layer dated to ~10,800 years ago. One of the middle bonebeds had an intermediate age ~4000 BP. Obviously, these bones were deposited too early to be the result of modern events. But how did they get there? Why are the so many of them? This is where taphonomy–the study of what happens to things after they’ve died–comes in. Are the long bones all oriented in the same direction by water flow? Do they show polishing or etching by stomach acids from a carnivore? Answers to these questions will point us in the right direction.

Unfortunately, we’re a little in uncharted territory here. Most of the techniques we use to understand bonebeds were developed in sites with large fauna (e.g., dinosaurs, bison, etc.), not microfauna. Do the same methods apply? How do you record orientation when the slightest nudge of the brush moves the tiny little bone you are trying to excavate? New technology may help. A few years ago, Russ Graham took a core with a large-diameter PVC pipe from a cave deposit in the Black Hills. He capped the ends, and once he returned to Penn State University, had it CT scanned. The scan showed tiny fragmented rodent skulls that would not have survived excavation. It preserved articulated elements and their orientations in situ. Perhaps this is the way to analyze the taphonomy of microfaunal bonebeds? That’s the next step in our bat cave work. I’ll let you know how it turns out.

Posted on January 18, 2014, in Bonebeds and tagged Bats, Cave Paleontology. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0